Wayne Kramer, damn. There was wisdom in those fingertips—from Chicago blues to free jazz cosmism, surf shred to psychedelic soul, Kramer and the MC5 synthesized the hardest, freest music of their day into a strutting, sweating, and inciting rock’n’roll. The MC5 could swing; but their preferred word for the basis of this music was drive—“the forward motion that a solid rhythm pounded out. Very Detroit.” The MC5 too were Very Detroit—first-generation bohemians from broken suburban homes, coasting on the limited prosperity of an auto industry boom that never quite happened for the Black working class, as urban “renewal” strategies only deepened racial disparity and civil unrest. Car-and-guitar guys turned to crime. In a militant cultural moment, even the name sounds like a revolutionary cell: the Motor City Five.

Because the Motor City Was Burning back then, as the MC5 affirmed in their massive rendition of John Lee Hooker’s twelve-bar broadsheet on the 1967 riots. And with full respect to the King of the Boogie, their live version is definitive: Rob Tyner’s feedback-kissed vocal is among his best, as Kramer and Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith’s rapport knows no distinction between lead and rhythm; blood brothers trading unattributable snarls.

The Halloween concerts that became Kick Out the Jams were no sock hop, and typical rock’n’roll exhortations are transformed in the song’s description of a midsummer melee. It’s not a gaggle of teenagers but the cops who “jump and shout” and “freak out,” pushed to exertion by the crowds they would constrain. And where Hooker’s original lyric has the singer leaving town (“I don't know what the trouble is/I can't stay around to find it out”), Tyner stands and taunts at the loosely choreographed but ill-prepared counterinsurgency; transforming reportage into one of the great anti-cop songs in a vast corpus. It’s also one of the best electric blues renditions in a decade of tepid appropriations—it takes guts to compete with Buddy Guy in 1968—hewing to the social form by way of common experience.

As John Lee Hooker watched the riots of July 1967 from his house in east Detroit, Wayne Kramer was returning to the city from a weekend getaway, to see pillars of flame along Grand River Avenue. In Left of the Dial, Kramer recalls the scene:

Cutting across town to get back to our apartments, we drove through an intersection where a police cruiser had struck a car full of black men. The cops were beating them across the intersection with clubs and flashlights. Broken glass and men’s hats were littered on the ground as the cops acted out a drama of hatred and rage. All across the city these scenes were played and replayed. On the second night it got worse.

On the last day of the riots, Kramer was arrested for having a telescope in the window of his house on Warren Avenue, and carried to prison in a tank. No charges were laid, but Kramer and the MC5 were emboldened in their far-left politics, fortifying their stake in a war-torn cityscape: “The insurrection was over, but its effect lingered for a long, long time. After that summer, it seemed everyone in Detroit bought guns.”

The mini-armoury of the group’s jam space is the stuff of rock lore; but it’s simply impossible to reduce the significance of the MC5 to drug-fuelled adventurism or a hip imposture, where they moved bodies and set the agenda for a generation of socially concerned artists to follow. Amid the embattled geography of Detroit and its intercultural exchanges, ‘Motor City is Burning’ became a second-hand manifesto for the group, almost a decade before the Clash would call for a riot of their own; moving in tandem with Caribbean youth after the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival riots. “I'd just like to strike a match for freedom myself,” Tyner sings: “I may be a white boy, but I can be bad, too.” Where loyalty to humanity means treason to whiteness, the MC5 announce their intent to dodge another, far more insidious, draft.

These were heavy, politicizing times; and amid escalating repression, there was nothing convenient about the MC5’s conversion to the hard left. Under the tutelage of their manager, John Sinclair, the MC5 entered the ranks of the White Panther Party—a Black Panther solidarity organization and mutual aid society convened after the encouragement of Huey Newton, operating within the Detroit Artists Workshop and the communes of Ann Arbor.

The White Panther Party was eclectic and their accompaniment was in many respects unsolicited, but there’s no doubt that they had skin in the game, enduring constant surveillance and interference. Sinclair himself became a cause célèbre after receiving an onerous sentence for selling two joints to an undercover police officer; though he was freed after two and a half years, following an extensive and high-profile public campaign. There’s a grimly funny morsel on the Please Kill Me website from Kramer: “Somebody asked John Sinclair once, Well, if you had it all to do over again John, what would you do? And he said, ‘I’d duck. Revolution comes again, I’m gonna duck.’”

In 1968, however, Sinclair and the MC5 did not duck. Sinclair’s management would place the MC5 in the thick of the mass movement against the Vietnam war—infamously coming to a head at their free concert outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. “Now here was a riot to be proud of,” Kramer recalls:

Coming from Detroit, we had seen our fair share of how the biggest gang in town could act and the Chicago Police Department was certainly the biggest gang in that town. The footage we’ve all seen a thousand times on TV, of demonstrators and police fighting in the streets, doesn’t do justice to the tangible fear … In the FBI surveillance films I’ve seen from the National Archives of our performance, it was shot by real pros. Good color, good camera angles. Nice job boys!

Sinclair and the MC5 would part ways on the cusp of his conviction, as the group’s former mentor became increasingly hostile, even refusing their contributions to his legal defence. (Kramer and Sinclair would later make amends.) But this fleeting collaboration resulted in some of the most integral political rock’n’roll ever created. “This is the real high society,” they crowed, connecting the subcultural imperative to ‘drop out’ with the injunction of an urban subaltern to Get Organized. Whatever the members of the MC5 thought of the White Panther Party platform individually, there can be no doubt that their music made a forceful, formal demonstration of real solidarity, exalting the Black vanguard of the 1960s in both politics and music.

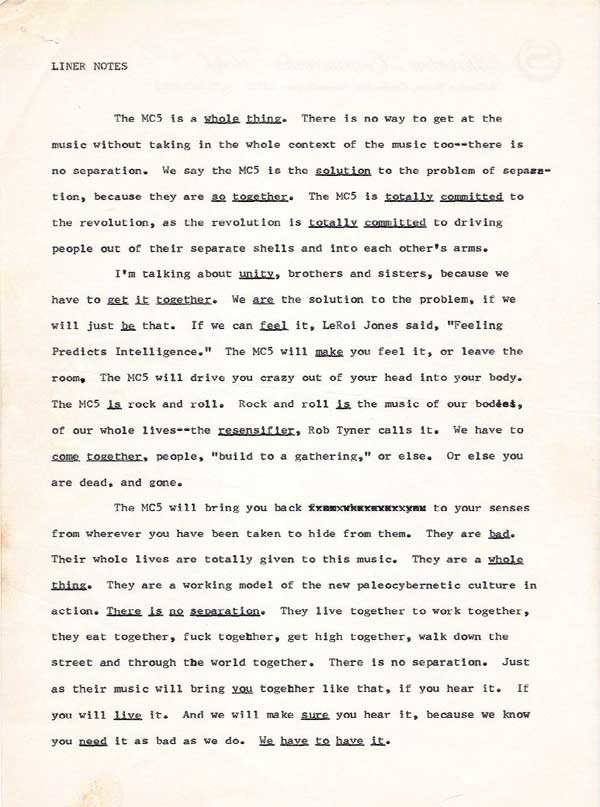

In observation and encouragement of this affinity, Sinclair’s liner notes for Kick Out the Jams still stand as one of the most powerful program guides in rock history: “The MC5 is a whole thing. There is no way to get at the music without taking in the whole context of the music too—there is no separation. We say the MC5 is the solution to the problem of separation, because they are so together.” It’s incredible to me that Sinclair somehow tricked Elektra Records into marketing this micro-essay in political ontology, wherein free love needs free time and property means death. Everything is everything, Sinclair decrees; and the crashing chords of ‘Come Together’ sound proof. “Let us form a link and move in rhythms,” Tyner howls, as the music draws the cheap affection of the age into a larger social experiment, making a wreath of its audience. Sinclair is clear about the cause of isolation that this music would reverse: “We are a lonely desperate people, pulled apart by the killer forces of capitalism and competition, and we need the music to hold us together.”

Kick Out the Jams convokes an Everybody; modelled on and moving through the music of the fused group. Earlier that year, the SI had written of the revolutionary need “to suppress all separations”—which goal, Sinclair suggests, as soon describes the synchronous assertion of raw power by the MC5, for whom “separation is doom.” In a fascinating reminiscence of his chemistry with Fred Smith, Kramer describes this feeling from within the music:

We developed a technique of playing together that's characterized as ego-loss. EGO-LOSS, where we would play whatever was appropriate to be played. Sometimes we would be playing syncopated rhythm parts, we could solo simultaneously and it really had to do with listening to each a great deal. We really could LOCK in on a really fundamental level. We played together for so long and we got to the point where our styles blended together. Even today, sometimes I'll hear our records and I'm not really sure who played what.

Whether twinning spirits or a minimal commune, Kramer and Smith made an ethical pact of their rock’n’roll—all for one and one for all—and the meaning of this ideal unity extends far beyond any stylish fraternity. That said, style is hardly beside the point, and the band conveys the coolness of rock’n’roll to the correctness of rebellion, revelling in the symbolic residue of a moulting society.

The MC5 could even make the stars and stripes look cool. (Don’t try this at home.) As Hendrix would raise the Star-Spangled Banner in an act of unavoidably ironic reverence—a performative contradiction, to follow Butler and Spivak’s discussion of undocumented immigrants singing the national anthem in Spanish—the MC5 imbued the symbols of a morally bankrupt nation with alternative intent, wrapping their weird trip up in a US flag as if a frat house or a biker gang had gone over to the revolution. Wayne Kramer’s own guitar becomes an emblem of the group’s bizarro USA; a custom Stratocaster with a patriotic finish that, beneath his fingers, would goad and soothe riotous participation in a music that represents the best, and the wretched, of America.

For all of their ambiguous pageantry, Kramer and co. saw through the American Ruse. The group’s second album, Back in the USA, is named for their hard-driving cover of the Chuck Berry song: “I'm so glad I'm living in the USA,” he sings. “Anything you want, we got right here.” But it’s not all hamburgers and jukeboxes, where Berry wrote the song upon release from a twenty-month stint in prison for violating the Mann Act; an artefact of racial and sexual panic which effectively criminalized extramarital relationships involving travel across state lines. Leaving aside the particulars of Berry’s situation, he wasn’t returning to a land of rock and honey from abroad when he wrote this homecoming lyric, but to a deeply racist society from a federal jail.

Kramer too was no stranger to this distinctly American experience. In the years after the MC5 went their own ways, Kramer supported his new project Radiation, as well as a full-time drug habit, by various schemes, until he was arrested in 1975 for selling to an undercover cop. Kramer would spend the next four years in FMC Lexington, where he continued to hone his craft, even apprenticing with bebop trumpeter Red Rodney—one of too many great jazz musicians whose careers were pocked with absences owing to nakedly discriminatory drug law enforcement.

The MC5 came up during the massive expansion of this project, as the experiences of Kramer, Sinclair, and their political models in the Black Panthers attest. There are many events of varying duration by which to mark the end of the “sixties,” including the cultural revolution of which the MC5 were a part; but I’d choose the commencement of the War on Drugs in roughly 1971 as a clear, periodizing benchmark. The MC5 are often said to have announced the punk era, as a crueller sequel to the falsely optimistic sixties; but they were victims as well as heralds of this transition, which was never just a matter of taste. The advent of punk coincides with the final years in which it was possible for much of a near-mythical “middle class” to anticipate progress; such that the alternative America one glimpses in the ceremony of the MC5 appears properly utopian: a no-place, never-was; and yet distantly perceptible in the energy of a counterculture soon to be repressed.

Kramer’s 2018 memoir, The Hard Stuff—named for his barnstorming solo debut in the mid-nineties—situates his music amid these vast developments. It’s a powerful, considerate chronicle of a career in fits and starts; an unsparing recovery memoir and a thorough refutation of the rumour that Kramer and the MC5 departed politics and denounced their former militancy after the White Panther era. This is partly based on Sinclair’s own pithy assessment of their split: “They wanted to be bigger than the Beatles, I wanted them to be bigger than Chairman Mao.” But Kramer writes with pride of his political dalliances, and with careful circumspection of his mid-career burglary years. It’s a true testimonial from one of the best ever to do it; another reminder of how much is missing from a world without Wayne Kramer. A crack in the universe appears, even a separation. But we have the music as a lesson, and as John Sinclair once wrote, “there is no way that it can be stopped now.”

RADIO STATE - February 5th 2024

Christian Muthspiel and Steve Swallow - Lullaby for Moli (Simple Songs)

Ellen Arkbro and Johan Graden - Postcard Greetings (single)

Robert Wyatt - You You (Comicopera)

Young Marble Giants - Searching for Mr Right (Colossal Youth)

The Spatulas - March Chant in April (March Chant)

Still House Plants - You Ok (Long Play)

Niecy Blues - Exit Simulation (Exit Simulation)

Dos - Do You Want New Wave or Do You Want the Truth? (Justamente Tres)

Eberhard Weber - Closing Scene (Pendulum)

The Durutti Column - Sketch for Summer (The Return of the Durutti Column)

Sonny Sharrock - Broken Toys (Guitar)

Susan Alcorn, José Lencastre and Hernani Faustino - Sombra (Manifesto)

Mary Halvorson - The Tower (Cloudward)